Your God is a lie. A sincerely held one, a soothing and useful one, but a lie nonetheless.

I don’t mean that to come across as accusatory or judgmental. After all, mine is a lie too. Our god‑concepts – mine included – are stories we tell ourselves in order to make life feel manageable. They bring order to chaos, meaning to suffering, and moral clarity to a world that stubbornly refuses to stay tidy. They help us sleep at night. And because they help all of us sleep at night, they are never merely personal. They are collective constructions — shared lies, if you like — held in place by culture, fear, habit, and inheritance.

That word “lie” may feel harsh, so let me qualify that. Our beliefs are almost never entirely false, and they are never entirely true. They carry fragments of insight, shards of wisdom, echoes of genuine encounter. But they are also shaped — often decisively — by psychological needs and sociological pressures far beyond our awareness or control. We inherit our gods long before we choose them.

Albert Schweitzer famously demonstrated that historical portraits of Jesus have an uncanny habit of resembling the age that produces them. Enlightenment Jesus was a moral rationalist. Victorian Jesus was a respectable gentleman. Liberal Protestant Jesus was a teacher of universal ethics. Apocalyptic Jesus emerged in moments of social upheaval. Each portrait revealed less about Jesus himself and more about the anxieties, hopes, and conflicts of the society gazing back at him.

In Schweitzer’s opinion, scholars did not find Jesus — they created him, then mistook their reflection for revelation. We have not outgrown this tendency; we have merely updated it.

The Jesus‑God of much contemporary Christianity looks remarkably at home in our world. He prizes order. He guarantees outcomes. He rewards the right people and disciplines the wrong ones. He values strength, clarity, certainty, and control. He rules. He judges. He wins. He represents a God who blesses nations, sanctifies violence when necessary, underwrites economic hierarchies, and reassures us that history is ultimately on our side. He is a stable parent, a caring boyfriend. He is decisive, efficient, and reassuringly predictable.

The gospels, however, make a claim that quietly detonates all god‑concepts. Jesus says, “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). Paul goes further: “In him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (Colossians 1:19). The writer of Hebrews agrees: Jesus is “the exact imprint of God’s being” (Hebrews 1:3).

If we take these statements seriously then we are forced into an uncomfortable admission: any picture of God that does not look like Jesus is an idol. Not a different interpretation. Not a complementary angle. An idol. And that includes many of our cherished, Scripture‑supported, theologically sophisticated god‑images.

What makes the God revealed in Jesus difficult to ignore is that he is not theoretical. He is visible, embodied, and profoundly unsettling. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus reveals a God who loves enemies (Matthew 5:44), refuses retaliation (Matthew 5:39), gives without calculation (Matthew 5:42), sends sun and rain on the just and the unjust (Matthew 5:45), forgives extravagantly (Matthew 6:14–15), rejects religious performance (Matthew 6:1–6) and refuses anxious control over outcomes (Matthew 6:25–34).

This God does not secure order through violence. He does not stabilise society by identifying enemies. He does not rule by threat, nor does he enforce justice as we instinctively imagine it should be enforced. Instead, Jesus reveals a God who absorbs violence rather than inflicts it, who exposes injustice by enduring it, and who overcomes evil not by defeating enemies but by forgiving them.

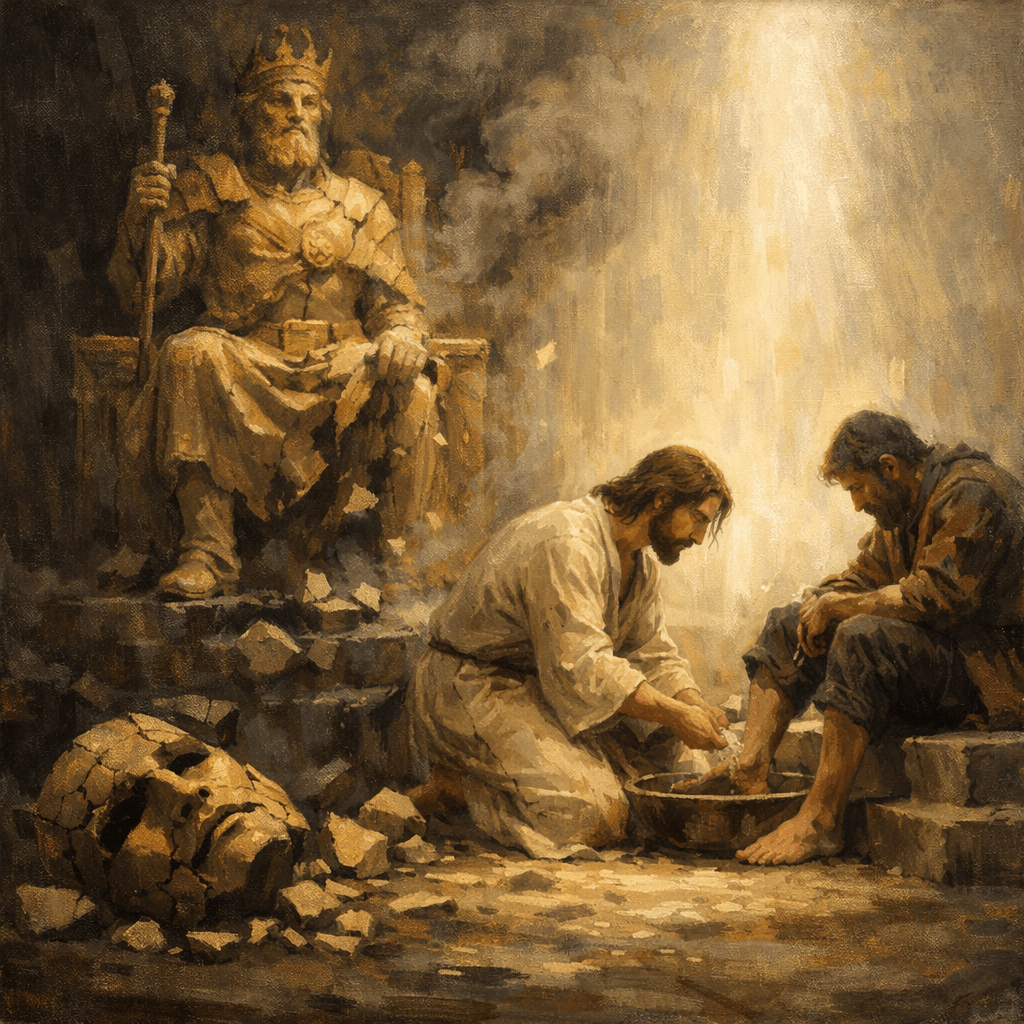

If Jesus reveals the fullness of God then God looks nothing like the God we want, the God we expect. Modern Christianity is saturated with the image of God as king. It is so familiar that it feels natural, even inevitable. God rules. God reigns. God sits on a throne.

Yet Jesus himself is remarkably ambivalent about kingship. When the crowds want to make him king, he withdraws (John 6:15). When Pilate asks if he is a king, Jesus redefines power so thoroughly that the question collapses under its own weight (John 18:36). When his disciples argue about greatness, he does not correct their hierarchy — he abolishes it: “The rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them… Not so with you” (Matthew 20:25–26). Jesus does not replace bad rulers with better ones. He replaces rule itself with service.

The God revealed in Jesus kneels. Which raises an awkward possibility: perhaps our preference for a ruling God says less about divine revelation and more about our fear of disorder, our craving for violent vindication.

It is a misconception about God that is reinforced by our insistence that the Scriptures stand alongside Jesus as a revelation of God. And there is certainly revelation in Scripture. But part of that revelation pertains less to the nature of the God who is than to an unveiling of our insistence on clinging to the gods who are not.

Scripture does not interpret itself. We do. And we interpret it in ways that reinforce the legitimacy of the idols we hold dear. Jesus repeatedly exposes this uncomfortable truth: “You have heard that it was said… but I say to you” (Matthew 5). Again and again, Jesus places his own way of being God over inherited readings of God — including readings explicitly grounded in Scripture. He does not deny the text; he rereads it through mercy.

This should caution us against confusing the Spirit’s voice with our interpretive instincts. Our readings are shaped by fear, culture, power, and survival mechanisms we rarely notice — let alone choose.

It is instructive to observe how Jesus responds when Scripture contradicts the God he claims to reveal. He does not denounce it, exile it, vilify those who defend it. He simply forgives.

It is not how gods usually respond to being misrepresented, how they react to being challenged. Forgiveness is certainly not how the gods would respond to being murdered. Imagine if humans had laid a hand in anger on Thor or Apollo. Gods do not forgive. They have status and power, which they wield with uncompromising authority. Perhaps that explains our fixation with God as a king. We want a God who is just like the other gods, only bigger and better. A God on steroids.

I would invite you to do something that might terrify you: briefly entertain the possibility that God is not a King. That your picture was all wrong. Put down the idol – if only for a moment – and explore a key Jesus statement through new eyes.In John 14:6, Jesus states: “I am the way, the truth and the life”. Habit has taught us to read that as a comparative religion slogan. Jesus, we want to believe, is asserting his Godhood by excluding any who will not yield to him. In modern times we have gone so far as to interpret this to mean that if you challenge Evangelical or Protestant Christian theological doctrine, you have no place in God’s Kingdom.

But Jesus is speaking to a Jewish audience immersed in debates about the yetzer hara and the yetzer hatov — the inclinations toward destruction and toward life. Deuteronomy had framed life with stark moral binaries: blessing for the righteous, curse for the unrighteous.

Jesus reframes the entire conversation. In Matthew 7, he rejects simplistic moral sorting. He warns against judgment. He insists that the measure we use will be used on us. Life is no longer found in identifying who deserves what, but in walking a path shaped by mercy.

When Jesus says he is the way, he is not claiming monopoly on God. He is revealing God’s character. The way is forgiveness. The truth is self‑giving love. The life is found not in vindication, not in sorting the righteous from the unrighteous, not in promises of blessing or curse, but in reconciliation.

Jesus reveals God not as a deus ex machina who intervenes to fix history, but as a forgiving victim who exposes its violence. This God does not bring justice as we expect it to happen. He brings healing where justice fails. He does not crush enemies; he creates siblings.

And — inconveniently — he invites us to walk the same path. Not to believe it. To embody it. To learn and practice a different way of being‑with.

Because in the end, the question is not whether our god‑concepts are sincere, orthodox, or deeply felt. The question is whether they look like Jesus. If they do not, then however comforting they may be, they are idols. And idols, as it turns out, are very good at helping us sleep — but very bad at teaching us how to love.

This is the most insightful & challenging article I’ve read on this site! No theologian has expressed a deeper dive into the revelation the Holy Spirit brings than this. Well done!

LikeLike