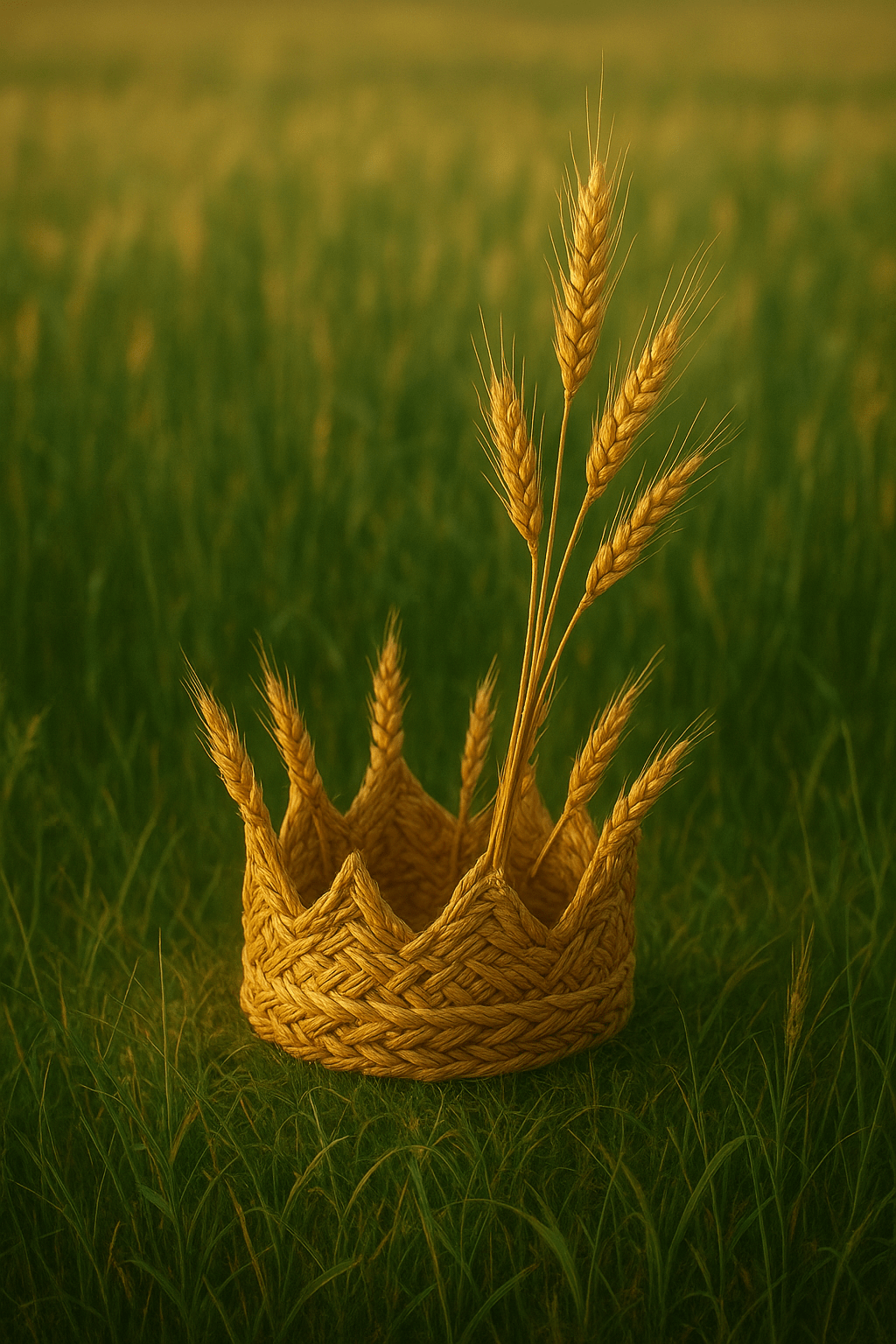

When we talk about God we reach instinctively for royal imagery because it feels weighty and majestic. Kingship promises order in a world fraying at the edges. And goodness knows we need that hope. Yet the startling claim at the heart of Christmas is not that God arrives as a king, but that God arrives to shatter the very idea of kingship itself.

If Jesus, as he claims, is the definitive revelation of the Father — “If you have seen me, you have seen the Father” — then we cannot speak meaningfully of God while bypassing the shape of Jesus’s life. And Jesus’s life is marked, again and again, by the refusal of power as domination. He is the un-king.

There is a small but telling moment in John’s Gospel: after feeding the five thousand, where the crowd is electric with messianic expectation. They try to seize Jesus and “make him king.” They want to enthrone him, to weaponise him. They want a leader who will vindicate their suffering and satisfy their longing for victory. Much like we do as we anticipate his second coming, watching for him to ride from the clouds on a glittering white steed to (finally) bring the principalities of the world to heel.

But Jesus walks away.

This is not shyness. It is not political caution. It is revelation. Jesus consistently resists the categories we try to impose on him, especially those rooted in hierarchy, triumph, and power-over. When his disciples argue about who is greatest, he tells them that the nations rule through power, but it must not be so among you. When James and John request thrones beside his own, he redirects them toward the way of self-emptying love. When Pilate presses him about kingship, Jesus demurs: “My kingdom is not from this world.” Not in the sense of being otherworldly, but in the sense of refusing the logic on which all kingship rests — rivalry, boundary, exclusion, the right to command. And when he describes his own vocation, he says simply: “The Son of Man came not to be served, but to serve.” There is no version of kingship that makes sense of that

René Girard helps illuminate a dimension often left unexplored: kingship is not merely about ruling; it is born from the ancient scapegoat mechanism. The king is both exalted and expendable — the one enthroned above the people but also the one who bears the community’s violence when tensions rise. The king stands inside the sacrificial machine as both beneficiary and victim, much like Hollywood celebrities or sports stars today.

Jesus sees this entire structure — the power, the prestige, the sacrificial shadow — and refuses it.

He exposes the mechanism rather than participating in it. “No one takes my life from me, but I lay it down.” That is the unmasking of the sacrificial order. No coercion. No mythic necessity. No divine will demanding blood. His death is not the crowning of a king within the old system but the unmaking of the system itself.

In rejecting kingship, he rejects both the top and the bottom of the hierarchy, both the ruler and the scapegoat. He steps outside the entire structure, and in doing so reveals a God who is not enthroned above humanity nor appeased by humanity, but one who stands among us in the vulnerability of love.

If Jesus is what God looks like, then God is not a king. God is not the sovereign who rules over subjects. God is not the manager of cosmic order. God does not demand service, allegiance, or tribute. God is the one who kneels. God is the one who washes feet. God is the one who empties Godself.

Jesus’s second commandment — to love our neighbour — is “just like” the first – to love God – because, in his life, they are indistinguishable. Love for God does not look like raising hands in worship or kneeling in prayer. It is not characterised by obedience to commandments or discipline in Bible study. Love for God is not moral purity or tithing regularly or subservience to leadership. To love God means to enter into a particular relational posture. And the posture is not royal. It is kenotic. It is mutual. It is the slow, patient, non-rivalrous giving and receiving of self.

If this ends up being my Christmas message because I do not find time to pen another, then I urge you this Christmas to let the manger speak more loudly than the carols. Trust me, I know that this is difficult. Carols are one of my favourite aspects of the season. I love the majesty and joy of the songs. I love the hope they make me feel. But “Glory to the newborn King” is misleading, no matter how beautifully or sincerely it is sung. The hope is in the manger. A manger is many things, but a throne it is not. It is an animal’s feeding trough — the space of the lowly, the overlooked, the very bottom of the social hierarchy. God begins there not to rise up the ladder but to dismantle the ladder altogether.

The birth of Jesus is the birth of a new way of being human — and, if Jesus is to be believed, the true revelation of what God has always been like too. It is an unsettling revelation because the implications are unmistakeable. God does not want kingship. God does not rule. God gives. And God invites us (rather than coerces us) into the same giving, the same self-emptying, the same mutuality.

The miracle at the heart of Christmas is not that we celebrate the arrival of a king, but the revelation that we are in relationship with a God who refuses to reign and instead calls us into a world where we, too, learn to live without domination or rivalry or fear. And that is worth singing about.

Leave a comment