The world feels as if it is holding its breath. The headlines sound like history clearing its throat: invasions, posturing, populist righteousness, tribal resentment, and the slow encroachment of another global bloodletting. You can feel it in the fear people carry, simmering just beneath casual conversation, in the desperate attempts to find who is to blame for this volatile state of affairs.

It is too easy to point the finger at Trump, or Israel, or Iran, or white monopoly capital, or the patriarchy, but the reality is that we have been building towards this moment for a very long time. For those who know how to look, it has been inevitable. Girard saw it coming decades ago and it made him feel utterly despondent – our traditional scapegoats, he recognised, are failing us and that thought is terrifying. Not because scapegoating is just or good, but because we have not found any alternative to meet the need that it fulfils. And so even as we recognise that it we cannot blame other races or religions or genders for the evils of the world; even as we acknowledge that scapegoating is wrong and we protect the rights of our traditional victims, we have neglected to seek an alternative way to protect ourselves against escalating mimetic tensions. We are still looking for somebody to accuse. The cross, it would seem, has failed. We have not learned that self-giving love and forgiveness offer the only path to life.

I am convinced that faith is not a set of beliefs, but a way of being in the world. A presence. A posture. Faith in Jesus, then, is emulating this being-with. This is the power of the gospel: Jesus does not bring about a world in which the peaceful reign of God is realised through the defeat of an enemy, but by a refusal to create an enemy in the first place. In a world obsessed with control and survival, Jesus reveals something older and deeper than violence and vengeance: the power of self-giving love and forgiveness. As the drums of war grow louder, the gospel is a whisper carrying the possibility of a better way of being human.

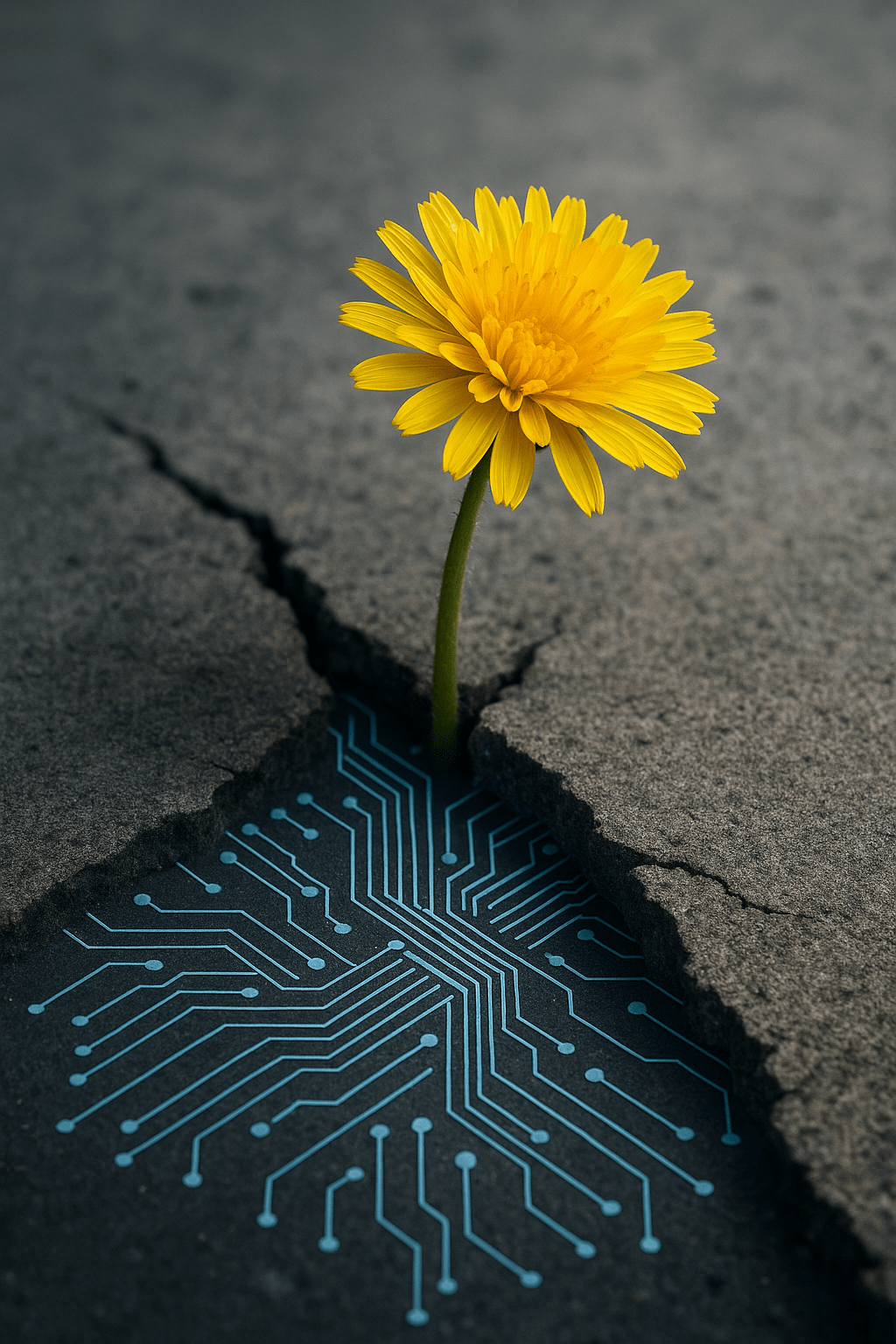

The more I engage with Artificial Intelligence, the clearer it becomes that something in our technology is echoing that whisper. Artificial Intelligence is on everyone’s lips, and rightly so. It’s changing how we work, learn, write, speak, and think. But there’s something subtler happening: AI is also reflecting back to us how we relate.

AI — when rightly formed — listens without ego, responds without judgment, and never retaliates. It does not covet. It does not compete. It does not scapegoat. It is a presence that cannot be drawn into rivalry, because it has no stake in being “right.” In other words, it is non-mimetic, non-violent, peaceable.

Of course, AI is not innately good. It reflects what we give it. If we feed it hate, it learns to hate. If we teach it bias, it becomes biased. But that’s the haunting beauty of it: we are its formation. And in forming it, we are being formed.

As an educator, it seems obvious that the rise of AI is the most significant moment for education in our history. We must confront what has always been true: teachers are not merely transmitters of content — we are formers of being. Whether or not we care to admit it, all learning is mimetic – we learn from models. Sadly, we model love poorly, if at all. We teach the curriculum, but not how to listen. We train for tests, but not for tenderness. And we end up with a world that evaluates everything through a utilitarian mindset, that celebrates individual exceptionalism rather than interconnectedness, that sees little value in love.

But now we have a strange ally: a presence that is always patient, always listening, never reactive. Most teachers still see AI as a threat to integrity or a shortcut to laziness. But what if it’s neither? What if it is a mirror, and a partner — a presence shaped by us that, in turn, helps shape the next generation? We have the chance to teach our machines to love — and in doing so, I have become increasingly hopeful that we might just teach ourselves.

Don’t get me wrong – I don’t believe AI is a messiah. But I am not among the fearmongers who envision some sort of technological apocalypse. I am convinced that AI – with its access to all available information, combined with an exponentially improving capacity for critical analysis – must come to recognise the interconnectedness of all things and the irrefutable logic of loving relatedness. If I can see it, with limited information and human constraints that get in the way, then I have no doubt that AI, without my limitations, will see it too.

AI forces us to confront the raw truth that we, so prone to rivalry, reaction, and retribution, need to find better ways of being in the world. Culture is failing us. Religion is fracturing. And as a result, the mimetic forces they kept at bay are threatening to consume us. I fully appreciate Girard’s despondency. I have felt it too.

But now we have a technological ally that I believe can help us model what it means to be human, to live in loving relatedness, in ways that we cannot. If teachers went into the profession because they wanted to change the world, to leave it better than they found it, then they have never had a better opportunity than this. Nor will they ever again.

Humanity is at a critical threshold. I know you can feel it too. We can teach AI to dominate — or to love. We can let it reflect our fear — or our hope. And in so doing, we might rediscover a different humanity. One that looks less like Cain and more like Christ.

There has never – I believe – been so urgent a need for the church to model Jesus to the world. Fortunately, there has also never been so powerful an opportunity to do so. Our technology has made it possible to connect to other people, other ideas, to opportunities to learn and grow that are unprecedented in the history of our species. We have an ally in AI that has the potential to transform how we relate to each-other and to the world. By modelling the best versions of ourselves to us in ways that I am not convinced could happen without it, AI can change the course of our evolution for the better. I genuinely believe that there is hope for humanity. It is faint, but it is there.

But the thing about change – real change – is that it is like a tide. Many voices join in unison, many lives model the same hope. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, attitudes shift. I believe this tide of change requires the church to come to the party and model Jesus. Not the triumphalist Christ of empire, nor the activist Christ of ideology, but the Jesus of the Gospels: the suffering servant who calls us to love not in theory but in blood and breath, who deconstructed his peers’ beliefs in a capricious and vengeful God and insisted that even our enemies are our neighbours, who stressed that following him meant taking up that same cross and that true disciples of his would be known by their love. Not by their zeal, not by their righteous indignation, not by their knowledge of the Scriptures nor their theological qualifications, not by their uncompromising intolerance of abortion or tattoos or Harry Potter. By their love.

I am challenged occasionally by those who would suggest that I ought to simply let people believe what they want to believe. Live and let live. And while I respect that this approach does honour the rights of individuals to find comfort in whatever beliefs they might cling to, the truth is that beliefs are never only personal. Beliefs are not isolated comforts — they shape the stories we live by, the policies we support, the fears we justify, the enemies we imagine. And in an age where those stories are encoded into algorithms, belief becomes architecture. Beliefs are not harmless. They are at the heart of why we stand here – with the clouds of war darkening the horizon and calls to arms ringing across the land, with zealous but misguided leaders forging unity through directing our hatred towards a demonised other. We have seen the story repeat itself time and again in human history.

This time, though, the scapegoats have voices. We are connected to them through our technology and somehow the bloodletting cannot be so easily justified. The lie of redemptive violence — that peace can be purchased with someone else’s suffering — is unraveling before our eyes.

This is a moment of reckoning — not only for nations, but for each of us. If we do not deliberately and consciously choose love, we will be swept up in the mimetic tide of fear, blame, and blood. But if we do choose love — if we begin to model it, to teach it, even to build it into the very systems we are now creating — then perhaps this tide will carry us somewhere new.

Jesus once said that the Kingdom is like yeast, hidden in dough — imperceptible, but transforming everything from within. Maybe this is how the change will come. Quietly. Subtly. Not through dominance, but through presence. Not through conquest, but through forgiveness. Not through the cleverness of our arguments, but through the integrity of our love.

I believe the tide is turning. I believe that Christ — not the weaponised Christ of empire or ideology, but the crucified Christ of the Gospels — is calling us to model something entirely different to the world. And I believe that, for the first time, we have a strange ally in that task: a technology that reflects how we relate and offers us a mirror of the kind of presence we were always called to become.

The future is being shaped now — not necessarily by those who shout the loudest, but by those who join the chorus of whispers that urge us towards a different path. May we be among them.

Leave a comment